When referring to “air quality”, we often think of smog, smoke, and other outdoor air pollution. However, we spend 90 per centi of our daily life indoors – in our homes, our workplaces, our schools, and other public spaces – so measuring indoor air quality (IAQ) is often Footprint’s focus when we’re working with clients to optimize building occupant health and wellbeing.

As the building industry gains more knowledge about how the built environment can affect our physical and mental health, green building certifications, such as LEED and WELL, will continue to improve how we can design healthier buildings to make safer places for everyone. As a team, Footprint receives regular questions from clients around LEED version 4.1 (v4.1) – specifically around credits linked to Environmental Product Declarations, Sourcing of Raw Materials, and Material Ingredients and Low Emitting Materials. A key element of all green building certifications is how we measure IAQ and reduce exposure to harmful components in products and materials.

The Biggest Threat to Indoor Air Quality.

It’s no surprise to those of us in the sustainable building industry that volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are one of the main components of indoor air pollution. Both engineered and naturally occurring chemicals, VOCs are emitted as gases from many common products in buildings, such as:

- Paints, coatings, adhesives, and sealants.

- Finish materials, such as flooring, ceiling systems, wall coverings, and millwork.

- Building materials, such as composite wood (plywood, medium density fibreboard), gypsum, and insulation.

- Furniture and equipment.

While some people, including children, the elderly, and immuno-compromised, are more sensitive to VOCs, their effect depends on a number of factors, including the level of exposure and the length of exposure. Think of it like entering a freshly-painted room – some people will get a headache, while others will simply think the smell is quite strong. Short-term exposure can cause reactions, such as eye, nose, and throat irritation, headaches, and fatigue. Prolonged exposure to higher concentrations of VOCs has also been linked to a wide range of chronic health problems, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, damage to liver and kidneys, and even cancer.

It’s a scary thought. In outdoor environments, VOCs (e.g., methane) are generally dispersed by air currents and thus don’t have a major effect on our health. Inside a building, however, concentrations of VOCs can be up to ten times higherii. That’s why green building regulations have been tightening up IAQ requirements to reduce the exposure to these harmful components.

Measurements and Monitoring VOCs.

We know that the level of VOCs in an indoor space is important as an indicator of IAQ, and the subsequent health and wellbeing of the building and its occupants. But even the “greenest” green building rating systems include 30-50 different chemicals – too challenging to monitor individually. To simplify the requirements for clients, LEED credits are based on standardized emissions testing for most products and material types, carried out by The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) Standard Method for the Testing and Evaluation of Volatile Organic Chemical Emissions from Indoor Sources Using Environmental Chambers, v. 1.2–2017.

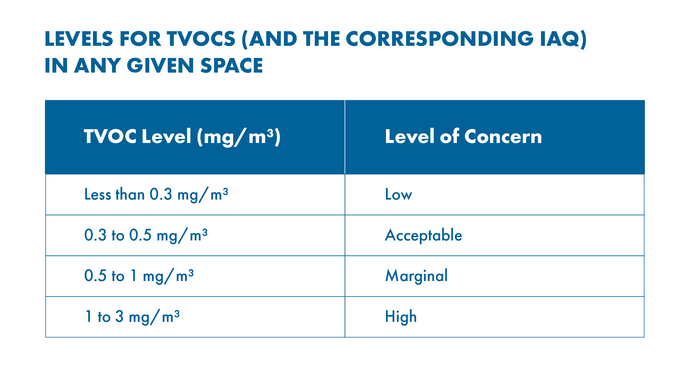

The strict testing process involves isolating products and materials in a chamber with a controlled temperature, relative humidity, and a constant inlet flow of clean air. Samples of the chamber air are collected and analyzed, determining the quantity (in micrograms) of VOCs per square metre of material per hour (Note: the type of VOC evaluation conducted is dependent on the type of material). This quantity is then converted to total volatile organic compounds (TVOC), which allows us to measure the overall level of VOCs (and the corresponding IAQ) in any given space.

Most green building rating systems award credits based on an acceptable or low TVOC level, as highlighted in the table below. If using a product that is higher than the amount indicated at a low level, then an alternative product must be sourced. Otherwise, the credit will not be achievable.

Footprint recommends products and materials that are certified at low or acceptable TVOC concentration levelsi.

Reducing TVOC Levels in Buildings.

Although entirely eliminating exposure to TVOCs is impossible, selecting low-emitting and non-emitting products when constructing or renovating a building, or fitting out a space, will significantly reduce the strength and quantity of indoor TVOC exposure – and gain those green building credits. We recommend that every project design team make sure the products and materials they are using has undergone an emissions evaluation, such as the CDPH evaluation that is widely agreed upon as the standard. In addition, a number of third-parties provide verified products.

When a product or material has these third-party certifications, like the examples above, an architect or owner can be assured that it meets green building standards for TVOCsii.

Improving IQ for IAQ.

While “wellness” is defined differently depending on who you’re speaking to (and how that person engages with the built environment), green building ratings systems help to set industry benchmarks for a healthy, energy-efficient, and economical green building. As these standards evolve with sustainable design and government environmental guidelines change, we work closely with clients to help them understand what is changing, why it’s changing, and what it means for their project. We balance wellness certifications and objectives with interior design, building efficiency, and long-term operational and leasing decisions to provide the best possible product solutions for every project. These materials can make a material difference.

Jessica Schlosser has successfully managed the sustainable certification of a vast portfolio of projects in both the private and public sectors. Her focus on sustainable construction processes and building materials, and involvement in the Canada Green Building Council’s Technical Advisory Group on Materials, offer a unique advantage on sustainability projects.

Sources